American voters can be forgiven for believing that they decide who wins elections when they go to the polls. But often this is just an illusion. In reality, who wins our legislative elections is usually determined years before, by the politicians who draw the lines of legislative districts. If they create a district that is 75% Republican and 25% Democratic, they have already established which candidate is going to be victorious. Gerrymandering is the intentional manipulation of district lines to predetermine election outcomes, protect incumbents, disempower voters, and unfairly benefit one party over another – a practice that is as unscrupulous as it is undemocratic. Adding to the shame of this situation is the fact that it is all so unnecessary. Most other developed democracies don’t have this problem – their election systems make gerrymandering impossible. It is time that we do the same.

How Gerrymandering Works

Every ten years, there is a national census and this usually requires redistricting – the redrawing of the lines of legislative election districts. Legislative districts are legally required to be close in terms of population. But people tend to move around. Some areas in a state, or regions in the country, gain population or lose population and so new district lines must be drawn in order to ensure that the districts have similar numbers of citizens.

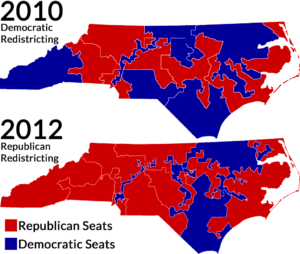

Redrawing these district lines for state and federal offices is usually done by state legislatures. And these politicians seem unable to resist the temptation to use this as an opportunity to gerrymander – to fix election outcomes by drawing those district lines in ways that benefits some candidates and parties over others. And a surprising number of them are willing to brag about it. For example, North Carolina State Senator Mark McDaniel once said: “We are in the business of rigging elections.” (And you thought it was the Russians who were rigging our elections!)

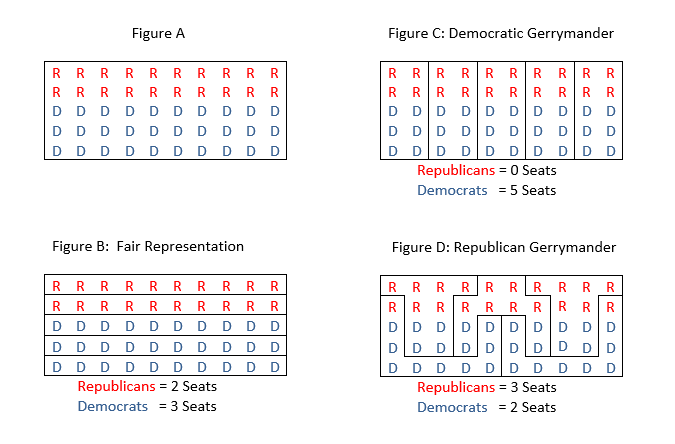

Here is a simplified example of how it works. Figure A shows a region in which five districts are to be drawn. One area, with about 40% of the vote, is Republican, and another, with 60% of the vote is Democratic. Fair representation would suggest that Republicans get 2 of the 5 seats (40%), and the Democrats 3 of the 5 seats (60%). This could be done by drawing the lines as in Figure B. But if the Democrats controlled districting they could gerrymander the district lines as in Figure C and win all the seats. Or if the Republicans were in control, they might draw their own gerrymandered districts, like Figure D, where they win the majority of the seats. So how many seats each party gets is not so much dependent on the votes the party receives, but on how the district lines are drawn. Quite a trick.

At its essence, partisan gerrymandering is the science of manipulating wasted votes. The dominant party draws district lines in a way that forces the rival party to waste large amounts of votes and thus be under-represented. Wasted votes are those that do not help to elect a candidate. There are two ways that votes are wasted. First, all votes for candidates who lose are wasted – they do not help to elect anyone. Second, and less obvious, are votes in excess of what a candidate needs to win. If a candidate gets 70% of the vote, 19% of those votes (all those over the 51% needed to win) are actually wasted because they don’t help that candidate to win.

Gerrymandering employs two techniques, each based on one of those kinds of wasted votes. In “cracking,” district lines are redrawn to ensure that the opposing party’s pockets of voting strength are divided up so that they become permanent minorities in most districts. This is what occurs in Figure C, where a concentration of Republicans is divided and turned into minorities in all the districts. Another strategy, called “packing” is used when the opposing party’s strength is too large to be completely divided. Instead, lines are redrawn to concentrate most of that party’s voters into a few districts so that many of their votes will be wasted in an overly large majority. This is shown in Figure D, where the two lower districts are 90% Democratic, which means lots of those votes go to waste. So the aim of cracking and packing is the same: to get one party to waste a lot of their votes and ensure that the other party wins more seats than it actually deserves.

Why Gerrymandering is Bad for Democracy

Gerrymandering violates several of the central tenets of democracy – especially fair representation and majority rule. The whole purpose of this tactic is to produce unfair representation. Specifically, the intention of partisan gerrymandering is to artificially increase one party’s number of seats and ensure its control over the legislative process. A particularly egregious example was the 2018 U.S. House elections in North Carolina. The Republican-dominated state legislature had redrawn the U.S. House district maps with gerrymandering as the explicit goal. And they were wildly successful. Even though both parties received nearly equal shares of the vote statewide, the Republicans were able to win 77% of North Carolina’s seats in Congress – 10 of 13 seats. Instead of being embarrassed by this blatant cheating, one the architects of the gerrymandering, state assemblyman David Lewis, lamented publicly that his only regret was being unable to draw a map producing “11 Republicans and 2 Democrats.”

Which party wins the most seats in the legislature may not be determined by how many votes that party gets, but instead by how the district lines are drawn.

In some cases, this intentional misrepresentation can be so extreme that the party drawing the lines can win the majority of seats in the legislature even if most voters support the other party. This has sometimes happened in state and even in federal elections. For example, in the 2018 elections for Wisconsin’s state assembly, the Democrats won more votes statewide than the Republicans, but the Republicans won 63 out of 99 seats. In the 2012 U.S. House elections, the Republicans came in second place nationwide with 1.4 million fewer votes than the Democrats. But thanks to creative and egregious gerrymandering in Republican controlled states, the GOP actually won the majority of House seats in that election. (This also happened in 1996 and perhaps in 2000 as well.) This put the party with minority support in the position to frustrate the policy agenda of President Obama. So which party wins the most seats in the legislature may not be determined by how many votes that party gets, but instead by how the district lines are drawn.

Voting Like North Koreans

Gerrymandering frustrates democracy in other ways as well. For one thing, it creates districts that are uncompetitive – districts in which voters are denied any meaningful choice. When legislators manipulate the district lines to create safe seats for Republican and Democratic incumbents, there are few real partisan contests. Instead of a healthy competition between two parties, we end up with a series of one-party fiefdoms in which a single party rules and voters feel helpless to change it. This disempowers voters. The New York Times once editorialized that as a result of gerrymandering, New Yorkers had “no more voting options than North Koreans have.”

Districts that are single-party dominated and uncompetitive have become rampant. In the 2016 elections for the U.S. House, only 33 of the 435 races were truly competitive – decided by a margin of 10% or less. Forty-two of the fifty states had no competitive contests at all for the U.S House. The average winner garnered 70% of the vote. These one-sided contests also discourage the higher voter participation necessary for a healthy democracy. Why go to the polls if your candidate doesn’t stand a chance in hell of winning? Or when your candidate will win no matter whether you vote or not?

To make matters worse, gerrymandering not only discourages voters from showing up, it sometimes discourages candidates from showing up as well. Safe districts are often so one-sided that the disadvantaged party does not even bother to put up a candidate. Parties are loath to waste their candidates and resources in districts where they have no chance of winning. So sometimes there is no contest at all and literally no real choice for voters. In the 2018 elections for the U.S. House, 43 major party candidates ran unopposed by the other major party. The situation is even worse on the state level. In recent elections, an average of 30-40% of the state legislative races in the U.S. had only one major party candidate. These elections are not so much races as prolonged victory laps by the preordained winners.

Getting Worse

The problem of gerrymandering is getting worse fast. Advances in technology has meant that, as Justice Kagan has put it: “These are not your grandfather’s gerrymanders.” In much of the past, gerrymandered maps were rough, hand-drawn affairs with a lot of guesswork involved. Today, we have sophisticated gerrymandering software, increasingly detailed data collection on voters, and professional gerrymandering consultants – which means that stealing seats from the other party has become a much more reliable and effective activity.

The political bias built into gerrymandering has also become worse because the national Republican Party has been funneling tens of millions of dollars into state legislative races with the express purpose of putting Republican state legislators in the position to gerrymander districts. In the 2010 state election cycle, the Republicans spent over $30 million dollars and picked up 700 additional Republican seats in state legislatures around the country. Not surprisingly, the new remapping of districts that took place after that allowed the Republicans to win a majority of U. S. House seats in 2012 with only a minority of the national vote.

Opening the Floodgates to Extreme Gerrymandering

In 2019, the Supreme Court made a decision in Rucho v. Common Cause that will encourage more widespread and extreme gerrymandering. The conservative majority on the Court acknowledged that gerrymandering is “incompatible with democratic principles,” but claimed they could find no constitutional reasons for interfering with gerrymandering. Which is strange considering that four lower federal courts had already ruled that excessive gerrymandering violated several aspects of the Constitution. They found that gerrymandering violated citizens’ First Amendment right of association and their Fourteenth Amendment right to equal protection. The Court also suggested that it could not act since there were no standards by which it can identify extreme partisan gerrymanders. This ignores a considerable body of empirical research establishing just such standards. Political scientists have devised several reliable statistical tests – one called “the efficiency gap” – that effectively show when egregious gerrymandering has taken place.

The effect of this ruling is that federal courts will no longer accept any legal challenges to even the most extreme forms of gerrymandering – thus encouraging even more states to engage in this kind of corrupt activity with impunity. The liberal minority on the Court passionately disagreed with the decision. As Justice Kagan, writing with what she called “deep sadness,” explained: “The practices challenged in these cases imperil our system of government. Part of the court’s role in that system is to defend its foundations. None is more important than free and fair elections.” Indeed, it is hard to think of a recent Supreme Court decision that has done more to imperil democracy in the United States.

The Hidden Problem: Unintentional Gerrymandering

However, things are even worse than they appear. Because there are actually two kinds of partisan gerrymandering: intentional gerrymandering and unintentional gerrymandering. The intentional version is what most people think of when they use the term “gerrymandering” and it is what has been discussed up until this point. But unintentional gerrymandering is also a serious problem. However, it gets little press, most Americans have never heard about it, and few have suggested any remedies for it.

“Intentional gerrymandering” as the term implies, is when map drawers intentionally shape districts to unfairly benefit one party over another. “Unintentional gerrymandering” is when districts are drawn according to neutral and apolitical criteria, and yet still inadvertently produce results that unfairly favor one party over another. The culprit is political geography – where one party’s voters are more geographically concentrated than the opposing party’s voters. In the United States, the Democrats are geographically packed into big cities, while Republicans are more spread out in rural and suburban areas. So even apolitical districting – with nice, neat, compact districts – is likely to create many urban districts with excessively large Democratic majorities, leading them to waste many votes. Republicans win in suburban and rural districts by much slimmer margins and thus waste fewer votes. The end result is that Democrats are systematically under-represented.

Studies have shown that even if we take humans completely out of the process, and create computer-generated neutral maps, the Democrats tend to get fewer seats than they deserve. Political scientists have estimated that over half the unfair advantage that Republicans enjoy in U.S. House elections is due to this unintentional gerrymandering. One study by FairVote found, for instance, that in the 2012 U.S. House elections, intentional gerrymandering cost the Democrats 9 seats, while geographical concentration and unintentional gerrymandering cost them 14 seats. So we really have two different problems of gerrymandering that need to be addressed in the United States. Not good news.

Other Democracies Do It Better

Interestingly, most other developed democracies do not suffer from any kind of gerrymandering. That is because they no longer use single-member districts for their legislative elections. Most use proportional representation (PR) voting systems. Instead of having many small single-member districts, they utilize fewer large multi-member districts – with say 10 to 20 legislators elected from a district. There are multiple winners in these districts, with parties receiving the proportion of seats that represents their proportion of the vote. A party that gets 30% of the vote, gets three seats in a 10-seat district. (For more about how PR works, see the article on winner-take-all elections.)

Proportional representation prevents gerrymandering in several ways. For one thing, even when population shifts, multi-member district lines do not have to be redrawn. If the population in a district grows, one need only add another seat or two; and if it shrinks, subtract a seat or two. No need to redraw districts – no opportunity to gerrymander.

How district lines are drawn in PR systems has no impact on how fairly parties are represented.

More importantly, gerrymandering relies on the manipulation of lots of wasted votes to work. Single-member district, winner-take-all elections always produce high numbers of wasted votes, typically over 40%. Multi-member district PR elections drastically reduce wasted votes to the range of 10% to 15%. Minor party supporters, for example, usually do not waste their votes in PR the way they do in winner-take-all elections. So even if a 10-member district is drawn so that a small party gets only 20% of the vote, those votes are not wasted, and that party gets 20% of the seats – 2 of the 10 seats. So how district lines are drawn in PR systems has no impact on how fairly parties are represented.

Importantly, PR gets rid of unintentional gerrymandering as well. It does not matter in a multi-member district if a certain party’s supporters are concentrated in a geographical area like a city. They will not waste their votes in over-large majorities, as happens in single-member districts. The more votes a party gets, the more seats it gets –irrespective of where its supporters live. The geographical distribution of voters has no effect on the fairness of party representation.

Even those few peer democracies that continue to use single-member district elections – Great Britain and Canada – do a better job of minimizing gerrymandering, at least the intentional version of it. Canada, for instance, had the same kind of gerrymandering problem as the United States until the 1960s, when laws were passed that put redistricting in the hands of provincial commissions. The commissions are typically made up of non-politicians like judges, political scientists, and retired civil servants. Great Britain has also taken redistricting out of the hands of members of parliament and created independent districting commissions.

Solutions for the United States

Since the Supreme Court has dodged any responsibility for fixing this problem, the search for solutions is now focusing on the states. Which is appropriate, given that this is where redistricting and gerrymandering take place. There are two approaches to reform on the state level. First are challenges to extreme gerrymanders based on state constitutions. Recently, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled that a redistricting map violated that state’s constitution’s free and equal elections clause – a principle found in many other state constitutions. Twenty-four states also have an equal protection clause similar to that found in the 14th Amendment, which could also serve as a basis for challenges to gerrymandered district maps.

The second state-level approach is the adoption of independent redistricting commissions for the U.S. House and state legislatures. In 2018, initiatives establishing such commissions passed in Colorado and Michigan. Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Jersey, and Washington already have these commissions. Taking redistricting out of the hands of self-interested politicians definitely makes a lot of sense. And it certainly will be helpful in reining in the worst kind of partisan gerrymanders.

But the commission approach does have a number of limitations, some serious. First, commissions are only likely to be established in states that allow for citizen initiatives – state legislators are unlikely to give up this power voluntarily. But these citizen-generated ballot measures are possible in only twenty-four states. In these other states, politicians are likely to remain in charge of this process. This could create a large political bias if the states that pass these initiatives are largely Democratic and the ones without them are mostly Republican. Democrats will be more restricted in their efforts to gerrymander, but Republicans will not.

Another issue with these independent commissions is how “independent” they really are. Many are more accurately described as “bi-partisan,” not independent, with equal numbers of Democrats and Republicans being appointed. Sometimes a few “independent” commissioners are also added on. These bipartisan commissions do eliminate one-party dominance in redistricting – which is good – but they can often produce what are called “sweetheart gerrymanders” in which both parties agree to create safe districts for their incumbents. The result is uncompetitive districts that leave voters with little power over who wins office.

Commissions may do little to address the systematic under-representation of Democrats caused by their concentration in urban areas.

However, the largest problem with the commission-based approach is that it does nothing about unintentional gerrymandering, which can be a large part of this problem. So even when the commissioners are truly independent and there is no attempt to create unfair representation, it may still occur because of the geographical distribution of different parties’ voters. In particular, commissions may do little to address the systematic under-representation of Democrats caused by their concentration in urban areas. Citing this problem of the uneven geographical distribution of voters, one of Britain’s leading political geographers, R.J. Johnston, pointed out that “Research in the United Kingdom in recent years has established that even with independent redistricting commissions and neutral rules and procedures, electoral bias is impossible to avoid.”

In the U.S., commissions’ inability to address unintentional gerrymandering helps to explain their mixed results. In California, 42 of the 53 U.S. House districts created by their commission were uncompetitive and dominated by one party. And the dominant party still won more than its fair share of seats. In Arizona, seven of the ten U.S. House districts created by their commission were not competitive at all. An analysis by FairVote concluded that: “The political geography of the United States might be helpful in explaining the lack of impact of Arizona’s … establishment of an independent redistricting commission.”

The Best Solution

Commissions are certainly a step in the right direction, and better than what we have now. But to truly eliminate gerrymandering in all of its forms in the U.S., we need to address the underlying cause of the problem: single-member district, winner-take-all elections. As long as we draw district lines where only one candidate wins and where large numbers of wasted votes are unavoidable, some gerrymandering is inevitable, if only unintentionally. As R.J. Johnston has concluded, it is doubtful whether “fair districting [can] be achieved in the U.S.A. or indeed anywhere that the plurality single-member constituency electoral system is used.”

PR gets rid of both intentional and unintentional gerrymandering in one fell swoop.

So the best solution is to abandon our current election system and adopt proportional representation elections for our legislatures – as most other large established democracies have done. As seen earlier, PR gets rid of both intentional and unintentional gerrymandering in one fell swoop.

PR also eliminates uncompetitive districts that can occur even when commissions draw the lines. Under this system, it is impossible for one party to have a monopoly on all the seats in a multi-seat district. Even minor parties with a small percentage of the vote are competitive and can win seats. So instead of a winner-take-all system, we would have an all-are-winners system, where all parties have a good chance to win some district seats.

When all districts are competitive for all parties, this encourages higher voter turnout. Supporters of third parties know they are not wasting their votes and can actually win some representation. And supporters of big parties know that the more votes their party gets the more seats it wins. PR greatly increases the incentive to vote, compared to winner-take-all systems.

The PR solution has some political feasibility, because it does not require a constitutional amendment. The Constitution gives states the right to decide how their members of the U.S. House of Representatives are chosen. Currently, a bill passed by Congress mandating single-member district elections for U.S. representatives is the only legal obstacle in the way of PR—and that law would have to be repealed. PR would not make sense for small states with only one or two U.S. representatives, but is eminently practical in states with larger House delegations.

The adoption of proportional representation in the United States would in one stroke cut through the Gordian knot of redistricting and gerrymandering. It would eliminate all the partisan brawling, stolen seats, and uncompetitive districts that plague our winner-take-all system. This is one, of many, reasons why PR is so popular among other major industrial democracies.

Chances for Reform: Very Good

One thing going for change in this area is public opinion. Support for reform among the public is very large and remarkably bi-partisan. Seventy percent of Americans, a majority of both Republicans and Democrats, want to rein in this lamentable practice. And citizens in some states are organizing to do something about it. In 2018, they passed redistricting commission initiatives in Colorado and Michigan, and similar grassroots efforts are springing up in other states. And at least some politicians have jumped on the bandwagon. When the Democrats took over the House in 2019, the first bill they introduced included a number of political reforms, including the mandating of independent state commissions for redistricting. With the Democrats now in control of the Congress and the presidency, momentum is building for this particular reform.

Unfortunately, there is little activity surrounding the most promising reform: the adoption of proportional representation elections that would completely eliminate the partisan gerrymandering problem in all of its forms. Most Americans have little awareness that our winner-take-all election system is at the root of our gerrymandering problems. And even fewer know what PR is, how it would eliminate gerrymandering, or how well it works in other democracies.

So right now, redistricting commissions seem to be the reform on the agenda. And with extreme gerrymandering threatening to spread even further, this approach deserves our support. Commissions may not be as good as PR in getting rid of this problem, but at this point, half a loaf is very much better than none.

read the next issue: 9. Outmoded Electoral College