A teacher once told me that something could not be “very unique.” “Either something is one-of-a-kind or it isn’t,” she said, “It can’t be ‘more’ unique than something else.” Nevertheless, the Electoral College may qualify as the “most unique” political institution in the world. No other democracy has seen fit to adopt this strange American method for choosing its chief executive. Could it be that they know something that we don’t? The answer is yes – this unique political institution is also uniquely and blatantly anti-democratic. Not surprisingly, even most Americans believe that we should get rid of this odd 18th century political relic.

How It Works

Our president is elected, not by the public, but by 538 electors. These electors are chosen on the state level. Each state gets one elector for each of its Senators, and one elector for each member of the House of Representatives (Washington D.C. also gets three of them). Each party puts up a slate of electors, and when we vote for the president, we are actually voting for that slate of electors. In all but two states, the electors all come from the party that wins the state vote for president. In two states, Nebraska and Maine, some of the electors are chosen by the separate voters in the U.S. House districts. In December of an election year, the electors meet in their respective state capitals and cast their votes.

To be elected, a candidate must win a majority – 270 votes. If no candidate receives a majority, the Constitution then stipulates that a “contingency plan” goes into effect. The House of Representatives chooses from among the top three candidates. Each state delegation in the House gets one vote, so the candidate with 26 or more votes becomes president. Disturbingly, a state’s House delegation does not have to support the candidate that won in their state. Two presidents have been elected this way, Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams.

Most Americans assume that electors must be chosen by popular vote, but there is nothing in the Constitution that requires this. The Constitution simply says that each state can select electors “in such manner as the legislature thereof may direct.” In the first forty years of the Republic, the state legislators themselves chose the electors, and there is actually no legal reason why they could not choose to do that again.

Origins of the Electoral College

The creation of the Electoral College is shrouded in a great deal of political myth. Many people like to believe that the E.C. was the product of long and careful deliberations by the framers of the Constitution. These wise founding fathers devised what they believed was the very best system for electing a president – the implication being that we should respect their considered judgment on this matter.

But the reality was much different and much less reassuring. At the very end of the Constitutional Convention, the exhausted framers spent barely a week deciding on how to elect the president. And the Electoral College was virtually no one’s first choice. One group of framers wanted Congress to elect the chief executive, as is done in parliamentary systems. But others were afraid that this would make the president too beholden to Congress and thus violate the idea of the separation of powers. Another proposal was to elect the president by popular vote. But this was strongly opposed by other framers who distrusted the masses. They viewed the public as an uneducated and irrational “mob” that could easily support undesirable candidates. As one delegate to the convention, Elbridge Gerry explained, “The people are uninformed, and would be misled by a few designing men.” (For more on the Framers’ distrust of democracy, see the article on the Constitution.)

Few of the framers defended the College as the best possible way to pick a president.

In the end, the Electoral College was settled on because (in the words of one of the framers) it was “the second choice of many delegates though it was the first choice of few.” It was chosen primarily because it was less objectionable than the other two choices. It didn’t give the power to choose the president to Congress but it still insulated the selection of the president from the public and their uninformed views. And many delegates felt more comfortable having the well-off and educated political elites in state legislatures choosing the chief executive. It is clear, however, that few of the framers defended the College as the best possible way to pick a president.

Why the E.C. is So Undemocratic

The Electoral College has several problems and violates a number of basic democratic principles. For example, the E.C. violates the principle of political equality – in particular the basic democratic principle of one person, one vote. It allows voters in small states to have more voting power than those in large states. The reason is that small states all get the minimum of three electoral votes (two for their Senators and one for their Representative) no matter how small their population. This means that in Wyoming it only takes 170,000 voters to elect an elector, while in California it takes 600,000. In this way, people in small states get more influence over who becomes president – and small states tend to be more conservative, white, and Republican.

But this small state bias is relatively modest compared to the enormous advantage that small states get in the Senate. It is estimated Republican presidential candidates get only about 20 more votes than they really deserve because of this bias. Most presidential elections are not close enough for this to matter. One case where it did matter was the 2000 election of George Bush, who won by only five electoral votes. The small state bias provided him with the winning margin.

However, the small state bias becomes much more exaggerated and much more of a concern if no candidate gets a majority of the electoral votes and the “contingency plan” goes into effect. Every state, regardless of its size, gets one vote. This means that small states with only 17% of the population would have the 26 votes necessary to elect the president. A clear and massive violation of the principle of equal voting power.

Equal voting power is a key requirement for fair and democratic elections, and the E.C. does not provide that. Most constitutional scholars agree that if the Electoral College were not in the Constitution, it would be found unconstitutional because of the way it undermines voter’s rights to equal protection under the law guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.

The main issue with the E.C. is that it can flagrantly violate one of the bedrock rules of democratic elections – majority rule.

Of course the main issue with the E.C. is that it can flagrantly violate one of the bedrock rules of democratic elections – majority rule. The most obvious example of this when the candidate that wins the popular vote loses to the second-place candidate – as happened with Hilary Clinton and Donald Trump in 2016, and Al Gore and George Bush in 2000. In rare cases, the small state bias mentioned earlier can be a contributing factor. But the main culprit here is the winner-take-all arrangement in most states. This enables the winning candidate to get all of the state’s electoral votes no matter what the margin of victory. This is what creates the disconnection between the popular vote and the Electoral College vote. The table below illustrates how this problem occurs.

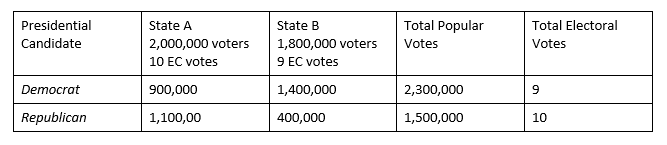

Table 1: How to Win the Popular Vote and Lose the Electoral Vote

The Republican ekes out a close win in the larger State A and gets its 10 electoral votes, while the Democrat wins by a landslide in the smaller State B and gets its 9 electoral votes. But the Democrat actually wins many more total votes 2,300,000 to 1,500,000. The problem is that many more of the Democratic votes were wasted in State A – 900,000 – than the Republicans wasted in State B – 400,000. (Large numbers of wasted votes and the misrepresentation this causes are inherent problems in all winner-take-all voting systems. For more on this, see the separate article on this site devoted to this voting system.)

The winner-take-all system in the E.C. also creates another problem: spoilers. Spoilers are independent or third-party candidates who take votes away from one major party and allow the candidate from the other party, who would have otherwise lost, to win the election. The classic example of a spoiler candidate is Ralph Nader in 2000. In Florida, Gore received 48.84% of the vote, Bush 48.85% and Nader 1.64%. Studies show that most of the Nader voters would have voted for Gore if Nader were not in the race. So a vote for Nader inadvertently helped Bush win. This allowed Bush to win Florida (and the Presidency) even though a majority of voters in that state – 50.48% — supported the leftist candidates. Clearly an unfair and undemocratic result.

Finally, the Electoral College also undermines democracy by discouraging voter participation. This again is the product of the winner-take-all nature of these elections. Most states are either primarily Republican or Democratic and there is little question of which way they will go on election day. If a state is mainly Republican, like Texas, it makes little sense for Democratic voters to turn out. Whether their candidate gets 25%, 30%, or 40% of the vote makes absolutely no difference and the larger turnout will still not win any electoral votes. Oddly, there is also little incentive for supporters of the dominant party to turn out and vote. They know they will win, so why bother to vote. Turnout tends to be higher in swing states where the race is close and could go either way, but there are relatively few of those.

Attempts to Defend the Electoral College

Defenders often argue that critics exaggerate the problems of the E.C. They say, for instance, that electing the candidate that takes second in the popular vote is very rare. It is true that it has happened only five times with the elections of John Adams in 1824, Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, Benjamin Harrison in 1888, George W. Bush in 2000 and Donald Trump in 2016. But why risk that disastrous outcome at all? Maybe more importantly, we have had 17 near misses – elections in which a shift of less than 75,000 voters in key states would have elected the candidate who came in second in the polls. The last time was with John Kerry in 2004, where a shift of 60,000 voters in Ohio would have given him the presidency while losing the popular vote. So we have just been lucky that it hasn’t happened many more times than it has.

A common defense of the Electoral College is that it protects the interests of the small states. It makes candidates pay attention to small states and their special interests, like farmers. There are several problems with this argument. First, it is not clear that small states have a separate set of interests from large states. Most farmers, for instance, actually live in large states like California and Texas. Second, presidential campaigns usually ignore small states. In fact they usually ignore most large states as well unless they happen to be a swing state.

Sometimes it is also suggested that getting rid of the E.C. would weaken federalism by de-emphasizing the role of states in the choice of the president. But in reality, the E.C. doesn’t really give the states a great deal of power. The power of the states is primarily maintained and encouraged by the Constitution, which restricts the powers of the federal government and gives the states the right to make their own policies in most areas. Getting rid of the Electoral College would not change that and would not undermine federalism in any significant way.

Unable to cite any real advantages to the Electoral College, many defenders spend their time trying to show why a popular vote for the presidency would be a bad idea. Some typical complaints are that a popular election would encourage widespread voter fraud or that it would necessitate frequent and expensive national recounts. Neither of these things is likely. In practice it is the E.C. which encourages fraud. The winner-take-all system in most states means stealing a few thousand votes in a close election could give all the state’s electoral votes to a particular party. But in a national popular election, stealing a few thousand votes in a few states would have practically no impact at all on the total vote count and the ultimate outcome.

Furthermore, the basic rule of thumb about recounts is that the smaller the voter base, the more likely a recount becomes. In a small town, for example, it is more likely that a small number of votes will separate the candidates, thus necessitating a recount. In state-wide or national level elections, the chances of a very close election necessitating a recount are relatively small. And even if a recount was necessary every so often, it would be a reasonable price to pay for all the benefits of electing the president by popular vote.

Other Democracies Do It Better

As mentioned at the outset, no other major democracy has chosen to follow our example and use an electoral college to elect its chief executive. Presumably this is because they are all too aware of the undemocratic problems built into this election system, and they have not been persuaded at all by the arguments of proponents of this system. So essentially the U.S. stands alone in clinging to this outmoded and undemocratic political institution.

The States Do It Better

If the Electoral College is such a great way for electing people to executive offices, why don’t we use similar systems to elect other executives, like governors on the state level? We could allocate electoral votes to counties, instead of states, and award them on a winner-take-all basis. The fact that no state actually does this is testament to how bad a political idea this really is. Every state has decided that electing governors by popular vote is a much better way to go. So, in the end, the Electoral College is actually doubly odd. It is odd in an international context, and it is odd domestically because it is not used for any other kind of election within the United States.

The Obvious Reform

The most obvious and logical solution to the problems of the Electoral College is simply to abandon it and use a nationwide popular vote. This is the way that we elect all the other executive offices in this country – governors, mayors, etc. In one stroke, this reform would restore many of the basic democratic election principles that the E.C. undermines. It would ensure equal voting power for all Americans, regardless of what state they lived in. The winner would necessarily be the candidate with the most votes, not a candidate who came in second place.

And we would get rid of swing states, because the vote outcome in close states would have no more impact than the outcome in other states. Candidates would campaign in many more states. A Democratic candidate, for instance, would find it useful to campaign throughout the South, where there are millions of Democratic votes to be had – even if they don’t represent a majority in those states. Finally, voter participation would be encouraged because even if you are in the minority party in your state, your vote can still help to elect your candidate president.

The only problem that a popular vote would not solve is that of spoilers. A third party or independent candidate could still take votes away from one major party candidate and give the election to the other. But this too is solvable. If there are three or more candidates and no one gets a majority of the vote, we can have a run-off election between the top two candidates. This eliminates spoilers. And if we used a voting system called “ranked choice voting,” we could even accomplish this without having to have a second election.

The main obstacle to this reform is that it requires a constitutional amendment to enact it. There have been many attempts to pass such an amendment, but they have all failed to get the necessary support of two-thirds of Congress and three-quarters of the states.

Some Bad Reform Ideas

Some have suggested ways of modifying the Electoral College voting process that could be accomplished without a constitutional amendment. One idea is to allocate electoral votes by district, instead of by state, as is done in Maine and Nebraska. This would eliminate the state-wide winner-take-all arrangements that cause many of the problems in the E.C. In this scheme, different candidates could win different district races in a state, and several could come away with some of the state’s electoral votes.

The district plan actually increases the chances of electing the “wrong” candidate.

While it sounds good, the district plan actually does not solve most of the problems of the E.C. If all states used this approach, it is still possible for the loser of the popular vote to win the presidency. This is because this plan does not really get rid of the winner-take-all situation that causes this problem. It would simply substitute many winner-take-all elections on the district level for one winner-take-all election on the state level. This actually increases the chances of electing the “wrong” candidate. The district plan would also not get rid of the small state bias, or the problem of spoilers.

Another proposal, using proportional representation elections for electors, also does not solve many of the problems of the Electoral College. Under this plan, electoral votes in a state would be allocated proportionally according to the percentage of the vote won by a candidate. So in a state with ten electoral votes, a candidate that wins 30% of the vote would get three of the ten seats. This does have the advantage of getting rid of the winner-take-all state arrangements, and it would also allow third party and independent candidates to win some electoral votes. But this would still not get rid of the small state bias. Also, it makes the problem of spoilers much worse by transferring it to the national level. Now third party and independent candidates could win enough votes to prevent any candidate from getting a majority. This would likely trigger the contingency plan where the election is then decided by the House of Representatives. This would be a political disaster. Each state, large or small, would get the same voting power – one vote. And the state House delegations would not even have to vote for the candidate that won their state. This might be avoided if a third-party candidate pledged his or her electoral votes to one of the major party candidates – but there is no guarantee that this would take place.

The Best Reform

The National Popular Vote Plan would solve most of the problems of the Electoral College.

There is, however, a new proposed reform that might allow us to have our cake and eat it too – to have all the advantages of a popular vote without having to change the constitution. It is called the National Popular Vote Plan. In this reform, states would pass bills pledging to give their electoral votes not to the winner in that state, but to the winner of the national popular vote. This idea takes advantage of the fact, described earlier, that the Constitution gives the power to allocate electoral votes to each state legislature. These bills would only take effect only when they are passed in enough states to constitute a majority of the electoral votes – 270 votes. In essence, this reform allows us to keep the Electoral College but modify it in a way that makes its outcome reflect the outcome of the popular vote. And like the conventional popular vote, this plan would solve most of the problems of the Electoral College – such as voter inequality, swing states, and minority rule. All in all, it is a very clever idea.

Chances for Reform: Increasing

Polls over the last 50 years have shown that a consistent majority of Americans want to abolish the Electoral College and switch to a popular election. This is a very hopeful sign.

To be fair, however, the support has become less and less bi-partisan over the years. In the 1960s, equal numbers of Democrats and Republicans – about 65% each – favored this reform. Thirty years later, 44% of Republicans ( and 73% of Democrats) still supported it. But in the wake of the EC helping to elect two Republican presidents who lost the popular vote, the degree of Republican support for reform has hit a new low of 32% in 2019. For some, clearly, self-interest now trumps any commitment to democratic values. Still, a majority of Americans would like to see the EC go.

Also, on the plus side, the problems of the Electoral College are also now getting a higher public profile. For example, many of the Democratic candidates for president in 2020 included Electoral College reform on their platform and mentioned it in their speeches.

In addition, the National Popular Vote plan promises to use the popular vote, but in a way that does not require a difficult to pass constitutional amendment. And there is growing interest in this reform. As of this writing, fourteen states and the District of Columbia have passed the plan – representing 189 electoral votes. If states representing 81 more electoral votes sign on, the plan will take effect. Ten years ago, the chances of reform in this area were practically nil, but with the introduction of the National Popular Vote plan, the likelihood of solving this problem has increased appreciably.

read the next issue: 10. The Two-Party Duopoly